In 2004, Africa’s journey to adopting electric vehicles (EVs) began when Cape Town-based company, Optimal Energy started working on the concept of a locally-made EV. By 2008, the company unveiled the Joule, Africa’s first locally manufactured EV at the Paris Motor Show.

Two years later, Optimal Energy piloted a small fleet of the Joule, a zero-emissions, six-seater, multi-purpose vehicle which consumed about 20% of the energy used by a conventional fuel-powered car.

There is a future for EVs in Africa. However, the market conditions and business models must be appropriate.

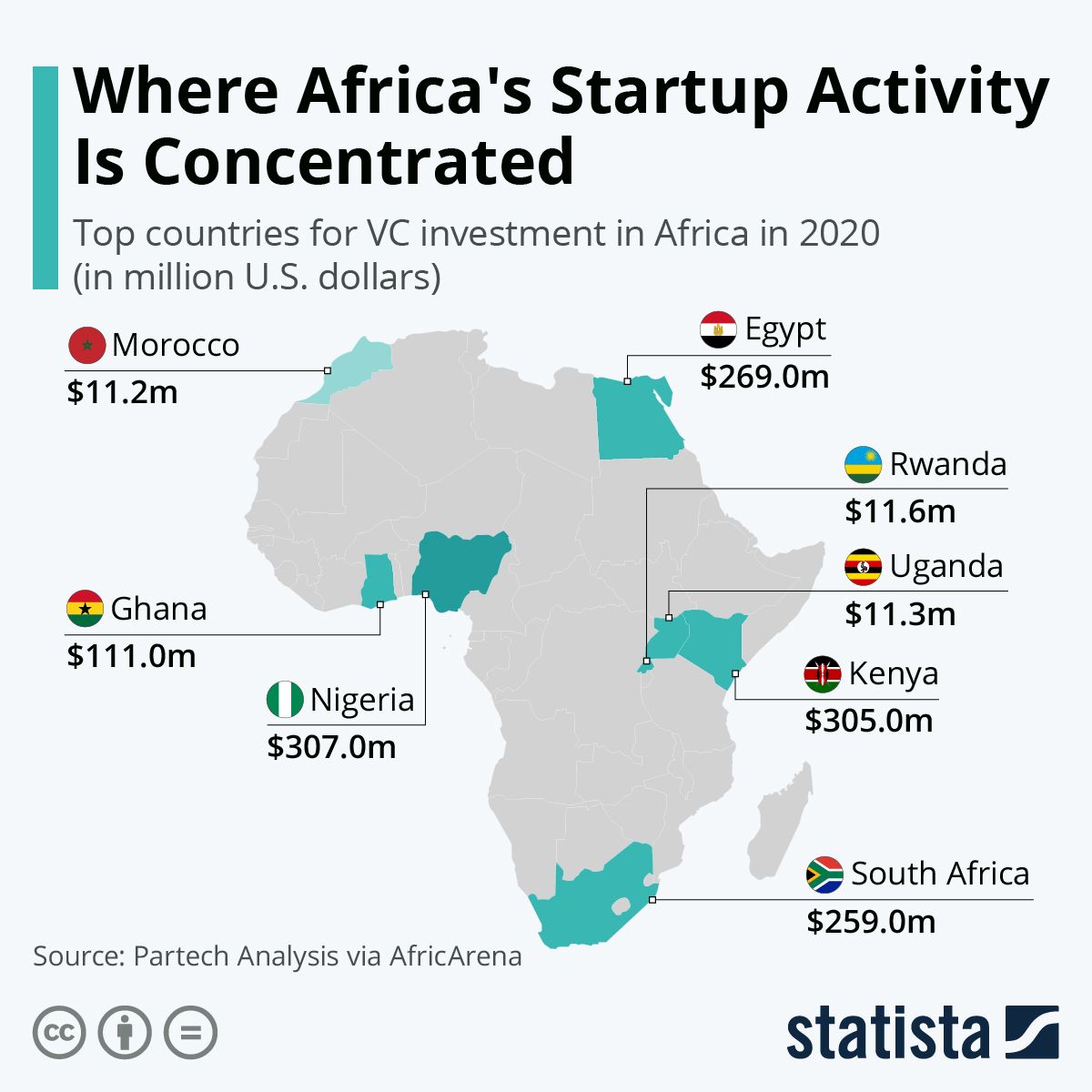

In 2021, Nigerian mobility startup Metro Africa Xpress (MAX) became Africa’s most-funded startup in the electric vehicle (EV) space when it raised $31 million in a series B round to expand into Ghana and Egypt. The company set a goal to provide vehicle-financing loans to more than 100,000 drivers over two years and build EV infrastructure in its new markets.

Years later the industry is still struggling because of high EV prices, unfriendly government policies, lack of charging infrastructure, high customs duties, and bad roads in African countries.

EV startups have found little success in Africa so far. In November 2022, NopeaRide, a Kenyan EV taxi service, stopped operations following the insolvency of Ekorent Oy, its Finland-based parent company and majority shareholder. About 6,000 out of the 12 million cars in South Africa are electric, and an estimated 350 of the 2.2 million vehicles in Kenya run on electricity. In comparison, globally, EV sales have skyrocketed globally, with 7.8 million EVs sold in 2022 — 68% more than the previous year. By the end of 2021, there were 16.5 million electric cars on roads worldwide.

Launched in 2015 as a logistics company, MAX pivoted to motorcycle ride-hailing in 2017. In 2019, MAX ventured into electric mobility. The company believes EV adoption in Africa will happen faster than in most parts of the world, David Hoyme, MAX’s international growth and expansion director, told Rest of World. Two- and three-wheelers will lead this revolution, he added.

Two and three-wheelers are cheaper and more affordable for users compared to four-wheelers. Also, due to the availability of charging and battery infrastructure, it has fastened the EV transition. A few factors will limit the scaling of EVs apart from the poor electricity supply on the continent. Different countries have different market dynamics, which means that EVs [will] grow at a different scale across countries.

In 2020, MAX debuted its electronic motorcycle, the M3, in Nigeria and later in Ghana. It is also testing its three-wheelers across Lagos with companies like Jumia, according to Hoyme, and has installed charging stations in hotspots across the city. Hoyme refused to share figures on the number of motorcycles MAX had sold or the charging stations it had installed.

It is so rare to see an electric car on the roads in Nigeria that those who own one become mini-celebrities. For instance, Nigerian tech entrepreneur Ezra Olubi said that driving around Lagos in his Tesla Model S Plaid can be a spectacle.

Source:

i) Rest of world (2023) Why African EV startups are struggling